Diluting Florida's Water Protection

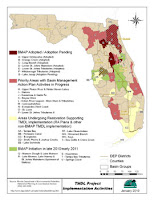

The Florida Legislature is now winding up its business, and one item of concern to environmentalists is House Bill 1445. It aims to make an end-run around the dozens of local governments that have enacted ordinances to restrict the sale and/or use of commercial fertilizer for residential applications. One would like to think that these cities and counties passed their laws out of altruistic concern for the environment. And it may be so, but they've definitely been motivated by pressure from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, though its attention to the quality of Florida's waters is somewhat belated. (Illustration: Map of Florida impaired waters)

After a lawsuit brought in 2008 by the Florida Wildlife Federation and Earthjustice contending that it was not enforcing compliance with the Clean Water Act, the EPA was forced to come up with "numeric nutrient standards" that would quantify the amount of pollution (nitrogen, phosphorus, fecal coliform, etc.) in Florida water bodies and to be more proactive in enforcing limits on its extent. These pollutants have many sources--storm water, car exhaust, agricultural runoff, atmospheric deposition, to name a few--and most are admittedly hard to control. But it's undeniable that people like living on the waterfront, and people like St. Augustine lawns, and the two are not a healthy combination, environmentally speaking. While it's true that residential fertilizers are not the whole problem, they're an important one--just look at a land use map and imagine the acres of lawn those blocks labeled "urban and built-up" represent--and they're one local governments can do something about.

Many Florida municipalities have wised up to the fact that it's a heckuva lot cheaper to keep pollution out of water than it is to clean it up later. They are worried the EPA will fine them or force them to start treating stormwater before it's released into rivers, bays, lakes and streams. That's expensive. Building and operating stormwater treatment plants is not something they want to do, especially in light of current budget shortfalls. A single alum-injection plant can cost millions of dollars. Proscribing the purchase and use of nitrogen- and phosophorus-containing fertilizers during the rainy summer months, and requiring the use of slow-release fertilizers all year, is a step local governments can take that costs taxpayers very little and has the potential to be effective in reducing non-point source pollution, especially in troubled watersheds with high population densities.

Enter the Florida Legislature, which aims to nip this trend in the bud. Florida is, after all, the land of phosphate, and fertilizer industry folks don't look kindly on laws that ban their product. The lawn care industry isn't too pleased, either, and the Legislature is responsive to business interests above all else. The House legislation now being proposed is insidious; it purports to promote clean water by mandating the "Florida-friendly" model landscape ordinance created in 2007 by the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation, the Florida Consumer Fertilizer Task Force, and the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Science. Sounds good, but the model ordinance is one-size-fits-all and was carefully crafted to mollify the fertilizer/phosphate/turf industry; even DEP says its "preference" is for a 2003 model ordinance which is much more comprehensive, addressing source controls, public education, and low-impact development. The 2007 model ordinance focuses primarily on "training and professionalism of professional applicators," not on application of fertilizer by homeowners, nor on the composition of said fertilizer. The House bill would require any local government that has water bodies defined as "impaired" by the EPA (sadly, a long list) to impose the Florida-friendly landscape model ordinance. And while the bill's language recognizes that local governments may find it advantageous to adopt more stringent standards and allows them to do so, it forces them to first jump through a lot of complicated hoops to prove that it is absolutely, positively necessary that they do so. Senate Bill 382, filed at the beginning of the session, originally contained similar language but, fortunately, it was stripped out by the Health Regulation Committee, leaving a statement that says, in effect, that the model ordinance is a darned good idea, and leaves it at that. The session isn't quite over, and HB1445/SB362 could still make it into law, including the provisions that hamstring local governments. It's not too late to contact your legislators and communicate your displeasure with it.

Whatever the Legislature decides about fertilizer ordinances, we can all help to stop nutrient pollution in our waterways. We can reduce or eliminate the amount of turf in our landscapes, fertilize the turf we have less often with a slow-release fertilizer or, best of all, ditch the fertilizer altogether (figuratively, not literally). And we can encourage our friends and neighbors to do the same. In this challenging economy, tell them they'll save money twice, once by not buying the fertilizer to begin with, and again in their tax bill, since their city or county won't have to pay to clean up the runoff later. Share some beautiful native wildflower seedlings with your neighbors and invite them to help you celebrate Florida's uniqueness. Tell them that a true "Florida-friendly" landscape uses native plants that are perfectly happy without any fertilizer, naturally adapted to our soil and climate patterns. With less turf and carefully chosen native landscape plants, not only will we all have cleaner water, we will have gardens that possess a "sense of place" and havens for birds, butterflies, and other wildlife. And that's so much more interesting and attractive than a perfectly coiffed lawn, anyway!

After a lawsuit brought in 2008 by the Florida Wildlife Federation and Earthjustice contending that it was not enforcing compliance with the Clean Water Act, the EPA was forced to come up with "numeric nutrient standards" that would quantify the amount of pollution (nitrogen, phosphorus, fecal coliform, etc.) in Florida water bodies and to be more proactive in enforcing limits on its extent. These pollutants have many sources--storm water, car exhaust, agricultural runoff, atmospheric deposition, to name a few--and most are admittedly hard to control. But it's undeniable that people like living on the waterfront, and people like St. Augustine lawns, and the two are not a healthy combination, environmentally speaking. While it's true that residential fertilizers are not the whole problem, they're an important one--just look at a land use map and imagine the acres of lawn those blocks labeled "urban and built-up" represent--and they're one local governments can do something about.

Many Florida municipalities have wised up to the fact that it's a heckuva lot cheaper to keep pollution out of water than it is to clean it up later. They are worried the EPA will fine them or force them to start treating stormwater before it's released into rivers, bays, lakes and streams. That's expensive. Building and operating stormwater treatment plants is not something they want to do, especially in light of current budget shortfalls. A single alum-injection plant can cost millions of dollars. Proscribing the purchase and use of nitrogen- and phosophorus-containing fertilizers during the rainy summer months, and requiring the use of slow-release fertilizers all year, is a step local governments can take that costs taxpayers very little and has the potential to be effective in reducing non-point source pollution, especially in troubled watersheds with high population densities.

Enter the Florida Legislature, which aims to nip this trend in the bud. Florida is, after all, the land of phosphate, and fertilizer industry folks don't look kindly on laws that ban their product. The lawn care industry isn't too pleased, either, and the Legislature is responsive to business interests above all else. The House legislation now being proposed is insidious; it purports to promote clean water by mandating the "Florida-friendly" model landscape ordinance created in 2007 by the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation, the Florida Consumer Fertilizer Task Force, and the University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Science. Sounds good, but the model ordinance is one-size-fits-all and was carefully crafted to mollify the fertilizer/phosphate/turf industry; even DEP says its "preference" is for a 2003 model ordinance which is much more comprehensive, addressing source controls, public education, and low-impact development. The 2007 model ordinance focuses primarily on "training and professionalism of professional applicators," not on application of fertilizer by homeowners, nor on the composition of said fertilizer. The House bill would require any local government that has water bodies defined as "impaired" by the EPA (sadly, a long list) to impose the Florida-friendly landscape model ordinance. And while the bill's language recognizes that local governments may find it advantageous to adopt more stringent standards and allows them to do so, it forces them to first jump through a lot of complicated hoops to prove that it is absolutely, positively necessary that they do so. Senate Bill 382, filed at the beginning of the session, originally contained similar language but, fortunately, it was stripped out by the Health Regulation Committee, leaving a statement that says, in effect, that the model ordinance is a darned good idea, and leaves it at that. The session isn't quite over, and HB1445/SB362 could still make it into law, including the provisions that hamstring local governments. It's not too late to contact your legislators and communicate your displeasure with it.

Whatever the Legislature decides about fertilizer ordinances, we can all help to stop nutrient pollution in our waterways. We can reduce or eliminate the amount of turf in our landscapes, fertilize the turf we have less often with a slow-release fertilizer or, best of all, ditch the fertilizer altogether (figuratively, not literally). And we can encourage our friends and neighbors to do the same. In this challenging economy, tell them they'll save money twice, once by not buying the fertilizer to begin with, and again in their tax bill, since their city or county won't have to pay to clean up the runoff later. Share some beautiful native wildflower seedlings with your neighbors and invite them to help you celebrate Florida's uniqueness. Tell them that a true "Florida-friendly" landscape uses native plants that are perfectly happy without any fertilizer, naturally adapted to our soil and climate patterns. With less turf and carefully chosen native landscape plants, not only will we all have cleaner water, we will have gardens that possess a "sense of place" and havens for birds, butterflies, and other wildlife. And that's so much more interesting and attractive than a perfectly coiffed lawn, anyway!

Comments